June 6, 2004

Was Dryden's first resident a squatter?

Amos Sweet, the first resident of Dryden, didn't get to enjoy his log cabin very long. It isn't entirely clear why, but he seems to have suffered from a problem common in the earliest days of Dryden: a land title that didn't hold up.

George Goodrich, in telling Sweet's story, takes the opportunity to discuss a reproduction cabin built for the Centennial Celebration as well as to reflect on the privations of the early settlers and their lack of cemeteries.

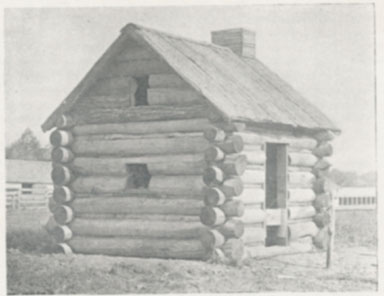

An 1897 reconstruction of Amos Sweet's Cabin.

Chapter IV.

The First Settlement.

It seems to be conceded that the first actual settler in the town of Dryden was Amos Sweet. Our information upon this subject is derived almost entirely from the "Old Man in the Clouds," the fictitious name of the author of a series of articles published in "Rumsey's Companion," the first newspaper published at Dryden, in the years 1856 and 1857, and which were, in fact, compiled by the editor from the information afforded by old men, then living, but since dead, and in that way preserved. We quote from the first number as follows:

"It was in the spring of 1797, that a man by the name of Amos Sweet came from the East somewhere, and, after ascertaining the location of his lot, put up a log house about ten feet square, just back of where now resides Freeman Stebbins [now John Munsey] in this village, where himself, his wife, two children, his mother and brother all lived. This would seem to be a very small and rude habitation to the people of our present gay and beautiful village. It was built of logs about a foot thick; these were halved together at the ends and the cracks chinked in with split sticks and mud. The house was eight logs high, covered with bark from the elm and basswood. Through one corner an opening was left for the smoke to pass through, there being no chimney or chamber floor. The fire-place was composed of three hardhead stones turned up against the logs for the back, and three or four others of the same stamp formed the hearth, these being laid upon the split logs which formed the floor. Inasmuch as there was no sash or glass in those days in this vicinity, their only window consisted of an opening about eighteen inches square cut through the logs, and this, to keep out the inclement weather, was covered with brown paper, greased over to admit the light. The door was also in keeping with the rest of the house, being composed of slabs split from the pine and hewn off as smooth as might be with the common axe. The hinges were of wood and fastened across the door with pins of the same material, serving the double purpose of cleet and hinge. In this house, thus built without nails and with benches fastened to the sides of the house for chairs, eating from wooden trenchers and slab tables much after the fashion of the door, did this little family of pioneers live."

But the title to the lot upon which Mr. Sweet built seems to have been defective and one Nathaniel Shelden appears to have had the real ownership, for in 1801, he compelled Mr. Sweet and his family to leave it. Elsewhere Mr. Sweet is spoken of as a "squatter", or one having no title, and Mr. Shelden is represented as using "fraudulent means" to dispossess him, but charity for both of these early pioneers compels us to believe that the difficulty grew out of the great uncertainty and confusion which then existed as to the titles derived from the old soldiers of the Revolution, some of whom had undertaken to sell the same lands several times over to different parties. At any rate Sweet was compelled to leave his pioneer home in 1801, and soon after, as the account says, "he sickened and died, and his remains, together with those of his mother and two children," were buried directly across the road from the Dryden Springs Sanitarium. The house remained for some time after, for we are told that it was used as the first school house for the children of the early settlers in the year 1804.

The new log cabin constructed during the summer of 1897 on the ground of the Dryden Agricultural Society was built of green chestnut logs and modeled after this first pioneer house in Dryden. It is intended to be preserved and it is hoped it will long remain as a relic of that kind of architecture, once so prevalent here, where now only the decaying remains of two or three log houses can be found in the whole township.

The fact that we now find no signs of the graves where Mr. Sweet and his family are said to have been buried, strikes us at first as singular, but a little reflection and an examination of the customs of the early settlers in that regard, supplies us with the explanation. The pioneers had too much to do to spend much time or effort in the burial of their dead and were too poor to go to much expense in such matters. Mr. Bouton, in his History of Virgil, says that the first grave-stone in that town was erected in 1823, although deaths had occurred there from its earliest settlement. He also explains their method of selecting places for the burial of their dead, which seems to us strange. We quote from pages 13 and 14 of the Supplement, where he speaks of a stranger who lost his way and perished in the woods, and mentions that he was buried near where he was found.

"Only a few families at this time (1798) resided in the town, which extended over ten miles of territory. There was no public burying ground and it was not possible to know where it would be located. * * * Families buried their dead on their own premises, and others, strangers and transient persons, were permitted to be laid in these family grounds. Ultimately it came to pass that one or more of these grounds came to be considered public, in a subordinate sense. There were a large number of them which continued in use after the public ground was opened."

Grave-stones as seen in the old cemeteries, where any existed at all, were then of the simplest character, many being made of native flag-stones, and the coffin of the pioneer was a coarse wooden box manufactured by the local undertaker, fifteen dollars paying for the very best.

When we come to think of it, a cemetery would not be much of an institution in an early settlement in the woods, especially where the living inhabitants had all they could do to keep soul and body together. Far different is it in a community of a century's growth, where now our cemetery tombstones, many of them imported from Italy and Scotland, represent the expenditure of many thousands of dollars, and the earth beneath them already envelops the forms of the ever-increasing, yet silent, majority.

Goodrich, George B. The Centennial History of the Town of Dryden, 1797-1897. Dryden: Dryden Herald Steam Printing House, 1898. Reprinted 1993 by the Dryden Historical Society. Pages 10-13.

(The Dryden Historical Society, which sells this book, may be reached at 607-844-9209.)

Posted by simon at June 6, 2004 8:54 PM in historyNote on photos